I found out yesterday that my PhD supervisor Dave Broomhead has died.

Dave was an amazing person and academic. For me, the thing that summed up Dave was his enormous faith in the goodness and ability of other people. His belief that everyone was doing their best may seem foreign to the competitive world of academia, where so many of us think our own work is the most important. But Dave's faith in others meant, not only that he was universally liked and respected by everyone he met, but that he could do research in a clear, methodological and honest way. I have many examples of his approach to life and academia, but those I give below are the ones that are most special to me.

When I started my PhD, I couldn't write. I had studied science and computing at school and University and never really got the hang of grammar or style. Dave took one look at the first draft of a paper I wrote and said "This isn't an article, its written like a computer program!". My feeling was that I was doing a PhD in maths, and writing was for journalists. Dave saw it differently. He set in place a Tuesday evening routine. We would go out and eat dinner together. He always paid. Then we would go back to his office. I would sit at his computer and he would lie flat on the floor behind me. He would ask me to read, line after line of the stuff I had written and make suggestions and corrections, not letting me move on until he was happy. The first two paragraphs of the 'Introduction' took about a month to write. I just reread

these paragraphs now and see that they sum up much of my research over the next 10 years. Through these evening sessions, Dave taught me not only to write, but to organize my thoughts and solve problems.

It wasn't just his PhD students, to whom Dave gave time and space. He always listened carefully to anyone who talked to him: family, friend, academic, cleaner, or random person in the pub. I once asked him to chair a session at a meeting at the Newton Institute in Cambridge. In many ways, Dave was the worst possible moderator. He never interrupted the speaker, even when they were 10 or 15 minutes over time. By the end of the session we were running 40 minutes late. Dave had asked if there were any last questions for the final speaker. He looked around. No takers. Finally, after a long pause he said the speaker"…..OK, could you put up your 5th slide again….as you said I think there could be an interesting consequence if you took in to account…." and so it went on. When I asked about it afterwards he lightly reprimanded me for my impatience: "if people have come all this way to give a talk then we have to let them tell us everything that is on their mind, otherwise we'll never understand anything."

This faith in others pervaded his thinking about how academia should be run. He was opposed to all the forms of evaluations, rankings and assessment exercises that went on during his time in Manchester. His basic assumption was that anyone working in academia was doing it because they loved it as much as he did. If his colleagues failed to publish anything, it was because they hadn't yet found something worth telling other people about. Why publish a paper unless you really has something worthwhile to say? Better to wait until you had really solved the problem, and no point harassing those who hadn't got there yet.

His own research was grounded in a patient respect for what others had done combined with an extremely deep thinking of his own. He invented a

whole new field of radial basis neural networks, because he was carefully going through and "spotted a simplification which the authors seemed to have missed". His influential work on

time series analysis, took an abstract part of topology, in the form of Taken's embedding theory, and solved problems in detecting and understanding chaotic signals. Last time I saw him present his research he was using

abstract algebra to solving computer communication timing problems. He used to joke that it didn't matter how 'pure' a mathematician thought their work was, he could take their work and make a useful application.

I last saw Dave three years ago, at home in Malvern with his wife Eleanor. I have seldom met two people with so much love and compassion for one another. I felt so much at home sitting in their house, talking to them both about their time as PhD students together in Oxford and their pride in their son Nathan. It is difficult for everyone when such an amazing person as Dave is lost, but his wonderful way of seeing life will never disappear.

|

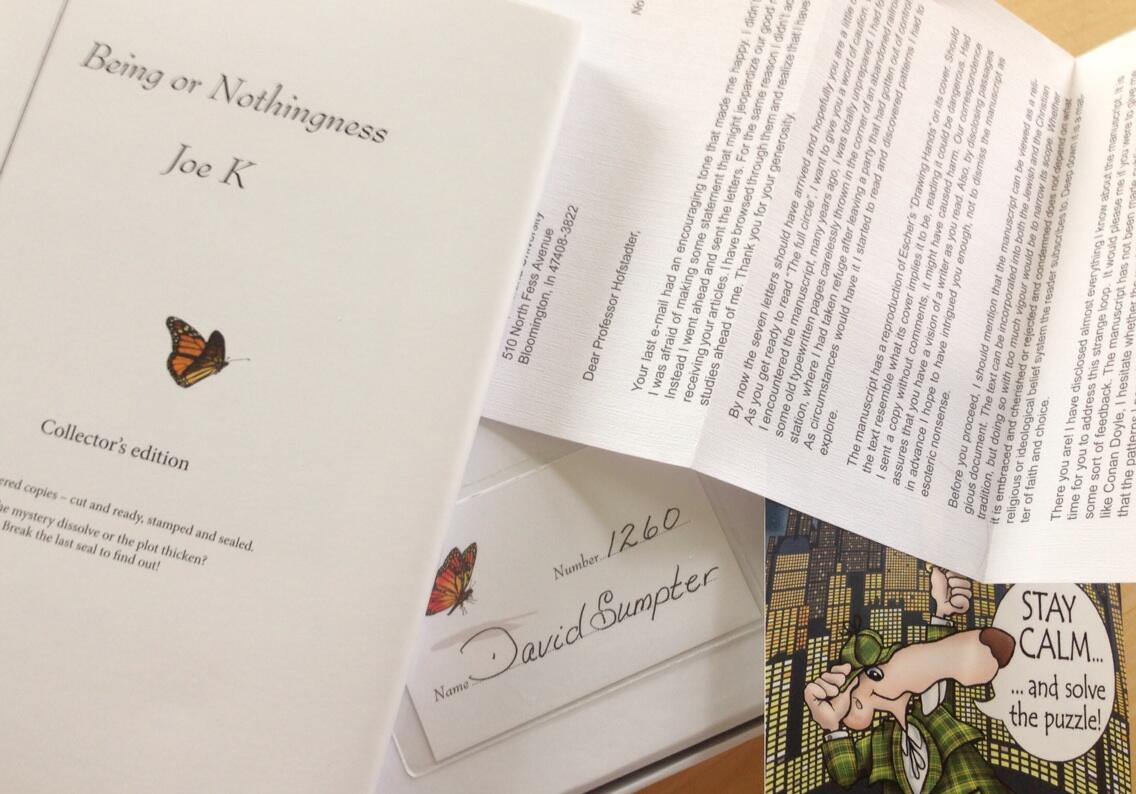

| Drawing by Dave, stolen by me from his Facebook page. |